(Published in The Huffington Post, September 10, 2013)

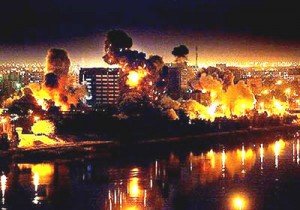

The looming military strikes on Syria are being justified as necessary to enforce and maintain a fundamental international law norm, namely the prohibition on the use of chemical weapons. It is quite clear that in the current situation, and in the absence of U.N. Security Council authorization, such strikes will also themselves violate a fundamental norm of international law, namely the prohibition on the use of force against sovereign states (see here for my own discussion of the legality issues).

At first blush the argument that one should violate the law in order to enforce it seems absurd, encouraging a counterproductive form of vigilante justice at best. But it does raise the question — are there times when we should violate international law in order to enforce it? Or more explicitly in the Syrian context: under what conditions and according to what criteria would it be justifiable to violate the fundamental rule prohibiting the use of force against sovereign states, in order to enforce the fundamental rule prohibiting the use of chemical weapons? Are there some practical responses that might provide some guidance for policy makers?

It must be acknowledged that there are some situations in which we accept that it would be justifiable to violate the law, or at the very least in which the circumstances would mitigate against our full condemnation of a violation. Such justification, in the form of exceptions, defenses, and reduced punishment, is indeed built into most domestic legal systems, and is part of most conceptions of justice.

Back in 1990, in the run-up to the Gulf War, I was a naval officer, and like most of the world, supported the need to use military force. As a student of history, I understood that force is sometimes necessary in the face of aggression.

Back in 1990, in the run-up to the Gulf War, I was a naval officer, and like most of the world, supported the need to use military force. As a student of history, I understood that force is sometimes necessary in the face of aggression.