(Published in the HuffPost, July 17, 2017).

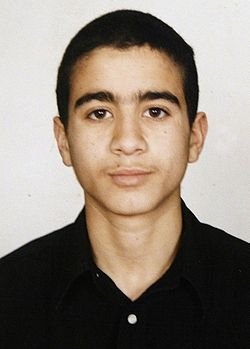

Much has been written both for and against the recent Khadr settlement, in which the Canadian government provided Omar Khadr with an apology and a $10.5 million payment. But the debate has largely focused on the wrong issue. Much of the discussion revolves around what Omar Khadr “deserves”—whether he deserved the treatment he received because he is a “confessed killer and terrorist”; or whether he now deserves the apology and payment because he is a “victim of torture and a denial of justice”.

As much as the settlement is about Omar Khadr and what he may deserve, it is more importantly about what Canada and Canadians deserve. An apology is not only for the benefit of the aggrieved, but for the integrity of the apologizer. Canada and Canadians deserves the atonement, the reaffirmation and restoration of our values, that is made possible by the settlement. Let me explain.

Canadian Values

The starting point has to be with our own values as a nation. What does Canada stand for, and what does it mean to be Canadian? We we are a liberal democratic country founded on constitutionalism, respect for human rights, and the rule of law. While the Charter of Rights and Freedoms has only been part of our constitutional system for some 25 years, surveys show that it has come to be the most significant determinant of Canadian national identity. This is likely because Canada has for much longer been a champion of international human rights, and international law more generally. In short, we are a nation that respects and embraces human rights.

Back in 1990, in the run-up to the Gulf War, I was a naval officer, and like most of the world, supported the need to use military force. As a student of history, I understood that force is sometimes necessary in the face of aggression.

Back in 1990, in the run-up to the Gulf War, I was a naval officer, and like most of the world, supported the need to use military force. As a student of history, I understood that force is sometimes necessary in the face of aggression.