(Published in The Conversation, Oct. 24, 2022).

Questions are being raised again about how the Canadian government makes decisions to use force or participate in armed conflicts, prompted by reports that special forces units of the Canadian Armed Forces were operating on the ground in Ukraine.

Questions are being raised again about how the Canadian government makes decisions to use force or participate in armed conflicts, prompted by reports that special forces units of the Canadian Armed Forces were operating on the ground in Ukraine.

While ostensibly deployed strictly for “training purposes,” such involvement can lead to more direct engagement in an armed conflict.

The decision to engage in armed conflict is one of the most consequential decisions a government can make. Who is involved in the decision-making, and what conditions or principles govern that process? Even more importantly, how should these decisions be made?

As a recent report suggests, the Ukrainian deployment has rekindled interest in these questions on Parliament Hill. But there should be a broader public discussion and debate.

Most Canadians would be surprised to learn that the prime minister and the cabinet have a far more unfettered power under the so-called royal prerogative to take the country to war than most other western democracies.

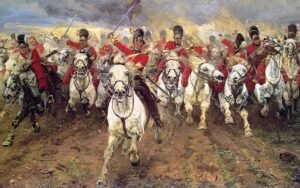

Early limits on war-waging powers

The modern idea that the power of the executive branch to wage war should be limited can be traced back at least as far as the Glorious Revolution in 1688, when English parliament placed constraints on the king’s ability to raise and maintain an army.