(Initially published on CBSNews.com, February 12, 2010)

From banking to healthcare, looking to Canada has become fashionable of late. It is also an example on equality rights. I served as an officer in one of the first Canadian warships to deploy with women among its crew. That was only after a spirited campaign waged by the military against the integration of women in combat roles, in part on the basis that they would undermine the cohesion and fighting effectiveness of combat units. There would be privacy issues, sexual tension, an erosion of the essential masculine warrior ethos, and ultimately a degradation of military effectiveness.

From banking to healthcare, looking to Canada has become fashionable of late. It is also an example on equality rights. I served as an officer in one of the first Canadian warships to deploy with women among its crew. That was only after a spirited campaign waged by the military against the integration of women in combat roles, in part on the basis that they would undermine the cohesion and fighting effectiveness of combat units. There would be privacy issues, sexual tension, an erosion of the essential masculine warrior ethos, and ultimately a degradation of military effectiveness.

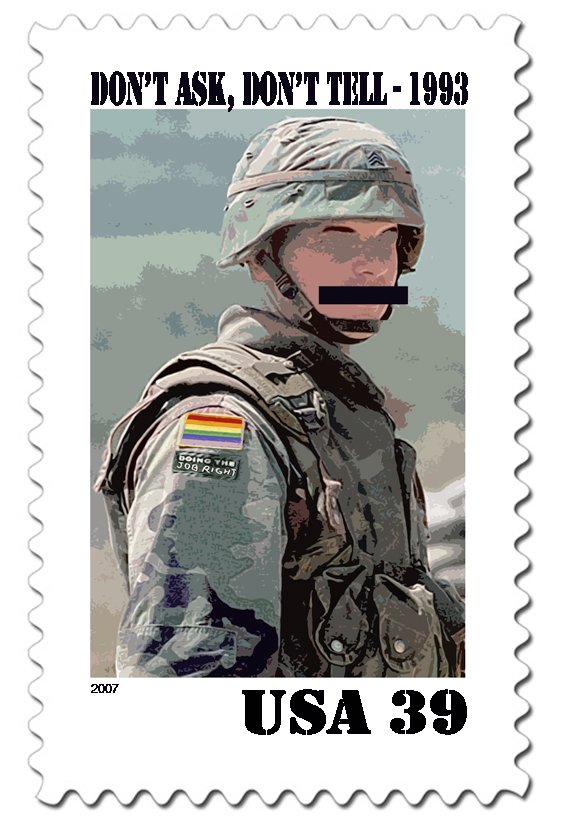

All of this was proved false of course. It was proved false again a few years later, in the early 1990a, when the Canadian military was again forced to adhere to the country’s constitutional values and open its ranks to openly gay and lesbian members. To the extent there was any disruption (and most studies have found there to have been none), it was minor and temporary, as the military sub-culture adjusted very quickly to the new reality – a reality that better conformed to the values of the society the military is sworn to defend.

The experience of Canada, Britain, Israel, Germany, Australia, and many other democratic allies of the United States (the troops of which are fighting alongside Americans in Afghanistan) have demonstrated that there is no significant impact on military effectiveness by the integration of gay and lesbian troops. Quite the contrary. As with the admission of women, and racial minorities before that, it broadened the recruitment base and increased the number of highly skilled personnel available to the military.