It was a pleasure to discuss in a podcast with Ayesha Malik of Dawn News in Pakistan a range of climate change issues, and in particular the ways in which contributions to climate change, and particular responses to climate change, may contribute to the risks of armed conflict.

It was a pleasure to discuss in a podcast with Ayesha Malik of Dawn News in Pakistan a range of climate change issues, and in particular the ways in which contributions to climate change, and particular responses to climate change, may contribute to the risks of armed conflict.

use of force

Geoengineering Wars and Atmospheric Governance

Published my latest article, written with Scott Moore of UPenn, “Geoengineering Wars and Atmospheric Governance,” in the The Harvard International Law Journal. A copy can be downloaded from SSRN here. Here is the abstract:

Published my latest article, written with Scott Moore of UPenn, “Geoengineering Wars and Atmospheric Governance,” in the The Harvard International Law Journal. A copy can be downloaded from SSRN here. Here is the abstract:

The increasingly harsh and unevenly distributed heat-related harms caused by climate change, together with frustration over the collective inability to respond to the crisis, are likely to make unilateral geoengineering efforts increasingly attractive. Stratospheric aerosol injection (“SAI”) is a form of solar radiation modification that is effective, technically feasible, and within the financial means of many states and even non-state actors. Yet, there are virtually no global governance structures in place to specifically regulate such activity, and existing international law would provide only weak constraints on unilateral SAI efforts. These features create incentives for unilateral action in what is known as a “free driver” problem: few constraints on a unilateral action that has low direct cost combined with immediate direct individual benefit despite widely distributed risks and indirect costs.

There would be significant collateral environmental and climatic harms associated with SAI. That, coupled with the high risk of unilateral action, is reason enough for both caution and stronger governance. But another risk posed by any unilateral SAI effort—one that is underappreciated and under-theorized—is that of armed conflict. We explore how and why states would likely perceive the potential risks associated with unilateral SAI effort as constituting a threat to national security, and in the absence of adequate legal and institutional mechanisms to constrain such unilateral action, might well contemplate the use of force to defend against the perceived threat. The Article explores and explains how and why the jus ad bellum regime is unlikely to prevent states from engaging in unauthorized use of force against unilateral SAI actors. (click “read more” below for full abstract).

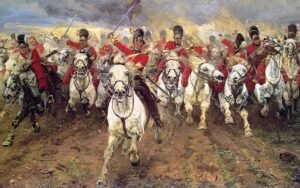

Canada’s ‘Royal Prerogative’ Allows it to Wage War Without Parliamentary Approval

(Published in The Conversation, Oct. 24, 2022).

Questions are being raised again about how the Canadian government makes decisions to use force or participate in armed conflicts, prompted by reports that special forces units of the Canadian Armed Forces were operating on the ground in Ukraine.

Questions are being raised again about how the Canadian government makes decisions to use force or participate in armed conflicts, prompted by reports that special forces units of the Canadian Armed Forces were operating on the ground in Ukraine.

While ostensibly deployed strictly for “training purposes,” such involvement can lead to more direct engagement in an armed conflict.

The decision to engage in armed conflict is one of the most consequential decisions a government can make. Who is involved in the decision-making, and what conditions or principles govern that process? Even more importantly, how should these decisions be made?

As a recent report suggests, the Ukrainian deployment has rekindled interest in these questions on Parliament Hill. But there should be a broader public discussion and debate.

Most Canadians would be surprised to learn that the prime minister and the cabinet have a far more unfettered power under the so-called royal prerogative to take the country to war than most other western democracies.

Early limits on war-waging powers

The modern idea that the power of the executive branch to wage war should be limited can be traced back at least as far as the Glorious Revolution in 1688, when English parliament placed constraints on the king’s ability to raise and maintain an army.

Geoengineering and the Use of Force

(Published in Opinio Juris, Jan. 20, 2021).

It is now widely accepted that the climate change crisis is going to contribute to increasing levels of armed conflict among and within states in the coming decades. Less widely considered is the effect the crisis may have on the jus ad bellum regime. In a two-part essay in Opinio Juris (and in a much longer law review article), I have suggested that there will be growing pressure to relax the jus ad bellum regime when the more dire consequences of the climate change crisis begin to manifest themselves. That is, there will be mounting claims that the threat or use of force may be justified against those “climate rogue states” perceived to be recklessly and unlawfully contributing to the growing threat to international peace and security.

It is now widely accepted that the climate change crisis is going to contribute to increasing levels of armed conflict among and within states in the coming decades. Less widely considered is the effect the crisis may have on the jus ad bellum regime. In a two-part essay in Opinio Juris (and in a much longer law review article), I have suggested that there will be growing pressure to relax the jus ad bellum regime when the more dire consequences of the climate change crisis begin to manifest themselves. That is, there will be mounting claims that the threat or use of force may be justified against those “climate rogue states” perceived to be recklessly and unlawfully contributing to the growing threat to international peace and security.

This argument may seem rather radical and unlikely from today’s perspective. But in this essay, I will examine how the case of geoengineering may help to illustrate just how some of the threats posed by climate change will create real tension for the jus ad bellum regime. The essay explores the hypothetical situation in which one country moves to unilaterally engage in a geoengineering scheme that many other states think will cause catastrophic harm to the climate and the ecosystem. How would the international community likely respond, and with what implications for international law?

Geoengineering

As most readers will know, the term geoengineering refers to large-scale intervention and manipulation of the environmental systems for purposes of either reducing the pace or countering the effects of climate change. There are many different avenues being explored, ranging from different methods of carbon dioxide removal (CDR), to various forms of solar management regulation (SRM). The latter is a broad category of methods that aim to lower or maintain the temperature of the Earth’s atmosphere by reducing the exposure of the Earth’s surface to the full brunt of energy from the sun.