In the latest episode of JIB/JAB-The Laws of War Podcast, I have a cross-posted episode in which I am the guest of Jonathan Hafetz on his Law and Film Podcast to discuss the film Eye in the Sky. It is a 2015 film likely known to most JIB/JAB listeners, about a joint British and American drone strike against al-Shabaab terrorists in Kenya, and which intelligently and engagingly explores the legal, ethical, philosophical, political, and strategic issues raised by the operation. We not only examine the film’s treatment of the legal issues implicated, including whether IHL should apply at all, and how the principles of distinction, necessity, proportionality, and precautions in attack are illustrated in the film, but we also explore the relationship between these principles and some of the ethical and strategic aspects of the decision-making in the film. We round out the conversation with a discussion of some other engaging films that similarly explore law in the context of armed conflict. I very much enjoyed the conversation!

In the latest episode of JIB/JAB-The Laws of War Podcast, I have a cross-posted episode in which I am the guest of Jonathan Hafetz on his Law and Film Podcast to discuss the film Eye in the Sky. It is a 2015 film likely known to most JIB/JAB listeners, about a joint British and American drone strike against al-Shabaab terrorists in Kenya, and which intelligently and engagingly explores the legal, ethical, philosophical, political, and strategic issues raised by the operation. We not only examine the film’s treatment of the legal issues implicated, including whether IHL should apply at all, and how the principles of distinction, necessity, proportionality, and precautions in attack are illustrated in the film, but we also explore the relationship between these principles and some of the ethical and strategic aspects of the decision-making in the film. We round out the conversation with a discussion of some other engaging films that similarly explore law in the context of armed conflict. I very much enjoyed the conversation!

JIB/JAB-The Laws of War Podcast Back On-Line

It was good to get JIB/JAB-The Laws of War Podcast back on-line after an almost 7 month hiatus! Started the new season with a fantastic new episode on the issues of sieges, the war crime of starvation, and the siege of Gaza, with Tom Dannenbaum of the Fletcher School of Law & Diplomacy at Tufts University. The podcast has now been listened to almost 44,000 times in over 120 countries, so it feels like it is worth continuing, notwithstanding how much work it is!

It was good to get JIB/JAB-The Laws of War Podcast back on-line after an almost 7 month hiatus! Started the new season with a fantastic new episode on the issues of sieges, the war crime of starvation, and the siege of Gaza, with Tom Dannenbaum of the Fletcher School of Law & Diplomacy at Tufts University. The podcast has now been listened to almost 44,000 times in over 120 countries, so it feels like it is worth continuing, notwithstanding how much work it is!

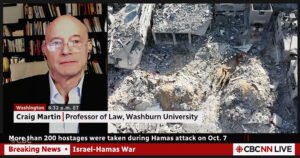

Speaking to the CBC on the Gaza Conflict

I was pleased that the media is reaching out to international law scholars to get explanations of the legal issues raised by the conflict in Gaza, and was happy to speak with the CBC’s Canada Tonight show on the topic despite how fraught the issues are, but I found it difficult to provide the necessary nuance or really explain the complexity of any of these issues in the short time provided. It is pity that there is not sufficient time to lay out the issues in a little more depth and sophistication. Some other media, such as Ali Velshi’s spot on MSNBC, have taken a little more time with experts to explain some of these issues more fully. It is important for the public to understand these issues better.

I was pleased that the media is reaching out to international law scholars to get explanations of the legal issues raised by the conflict in Gaza, and was happy to speak with the CBC’s Canada Tonight show on the topic despite how fraught the issues are, but I found it difficult to provide the necessary nuance or really explain the complexity of any of these issues in the short time provided. It is pity that there is not sufficient time to lay out the issues in a little more depth and sophistication. Some other media, such as Ali Velshi’s spot on MSNBC, have taken a little more time with experts to explain some of these issues more fully. It is important for the public to understand these issues better.

Speaking on Rights-Based Climate Change Litigation at Case Western

It was a pleasure to speak at the ABILA-sponsored conference, Climate Change and International Law at a Crossroads, at Case Western Reserve Univ. School of Law. I presented a paper on the significance of rights-based climate change litigation, on a panel that included Michael Kelly and Victoria Haneman of Creighton Univ. Law School, Alexander Pearl of Oklahoma Univ. Law School, and Rebecca Hamilton of American Univ. Law School. The panel discussion was great, and the rest of the conference was outstanding, with keynotes from Chile Eboe-Osuji of TMU Law School and former President of the I.C.C., and John Knox, former U.N. Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and the Environment.

It was a pleasure to speak at the ABILA-sponsored conference, Climate Change and International Law at a Crossroads, at Case Western Reserve Univ. School of Law. I presented a paper on the significance of rights-based climate change litigation, on a panel that included Michael Kelly and Victoria Haneman of Creighton Univ. Law School, Alexander Pearl of Oklahoma Univ. Law School, and Rebecca Hamilton of American Univ. Law School. The panel discussion was great, and the rest of the conference was outstanding, with keynotes from Chile Eboe-Osuji of TMU Law School and former President of the I.C.C., and John Knox, former U.N. Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and the Environment.