In this episode I discussed the question of whether it is possible now, while hostilities are still ongoing, to assess whether some aspects of the IDF’s conduct of hostilities may be in violation of IHL, with two of the top experts on the issues: Janina Dill of the University of Oxford and Adil Haque of Rutgers Law School. For more on the episode, including all the supporting reading material, visit the website!

In this episode I discussed the question of whether it is possible now, while hostilities are still ongoing, to assess whether some aspects of the IDF’s conduct of hostilities may be in violation of IHL, with two of the top experts on the issues: Janina Dill of the University of Oxford and Adil Haque of Rutgers Law School. For more on the episode, including all the supporting reading material, visit the website!

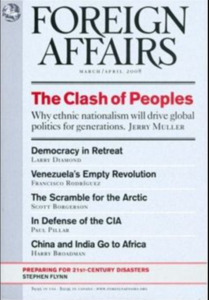

Foreign Affairs Essay – The Battle Over Blocking the Sun

My colleague Scott Moore and I published an essay in Foreign Affairs that summarized some of the arguments that we make in our forthcoming law review article in the Harvard International Law Journal. The essay (with a title we did not love) is “The Battle Over Blocking the Sun: Why the World Needs Rules for Solar Geoengineering,” Foreign Affairs, Aug. 14, 2024. The argument is captured in the abstract to our much longer law review article, “Geoengineering Wars and Atmospheric Governance,” Harvard International Law Journal (forthcoming, 2025), which is here:

My colleague Scott Moore and I published an essay in Foreign Affairs that summarized some of the arguments that we make in our forthcoming law review article in the Harvard International Law Journal. The essay (with a title we did not love) is “The Battle Over Blocking the Sun: Why the World Needs Rules for Solar Geoengineering,” Foreign Affairs, Aug. 14, 2024. The argument is captured in the abstract to our much longer law review article, “Geoengineering Wars and Atmospheric Governance,” Harvard International Law Journal (forthcoming, 2025), which is here:

The increasingly harsh and unevenly distributed heat-related harms caused by climate change, together with the frustration over the collective inability to respond to the crisis, are likely to make unilateral geoengineering efforts increasingly attractive. Stratospheric aerosol injection (SAI) is a form of solar radiation modification that is effective, technically feasible, and within the financial means of many states and even non-state actors. Yet there are virtually no global governance structures in place to specifically regulate such activity, and existing international law would provide only weak constraints on unilateral SAI efforts. These features create incentives for unilateral action in what is known as “free driver” problem —few constraints on unilateral action that has low direct cost combined with immediate direct individual benefit and widely distributed risks and indirect costs.

There would be significant collateral environmental and climatic harms associated with SAI. That, coupled with the high risk of unilateral action, is reason enough for both caution and stronger governance. But another risk posed by any unilateral SAI effort—one that is underappreciated and under-theorized—is that of armed conflict. We explore how and why states would likely perceive the potential risks associated with unilateral SAI effort as constituting a threat to national security, and in the absence of adequate legal and institutional mechanisms to constrain such unilateral action, might well contemplate the use of force to defend against the perceived threat. The article explores and explains how and why the jus ad bellum regime is unlikely to prevent states from engaging in unauthorized use of force against unilateral SAI actors.

Guest on Energy Policy Now! Podcast – Managing the Geopolitical Risks of Solar Geoengineering

My colleague Scott Moore and I were guests on the Energy Now! Podcast, produced by the University of Pennsylvania’s Kleinman Center for Energy Policy, for an episode entitled “Navigating the Geopolitical Risks of Solar Geoengineering,” to discuss our law review article on this topic forthcoming in the Harvard International Law Journal, and shorter essay on the subject in Foreign Affairs.

My colleague Scott Moore and I were guests on the Energy Now! Podcast, produced by the University of Pennsylvania’s Kleinman Center for Energy Policy, for an episode entitled “Navigating the Geopolitical Risks of Solar Geoengineering,” to discuss our law review article on this topic forthcoming in the Harvard International Law Journal, and shorter essay on the subject in Foreign Affairs.

The Power of Rights-Based Climate Change Litigation

My law review article exploring the influence and impact of rights-based climate change litigation has now been published in the Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law, and the full article can be downloaded from SSRN. The abstract is posted below:

My law review article exploring the influence and impact of rights-based climate change litigation has now been published in the Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law, and the full article can be downloaded from SSRN. The abstract is posted below:

An increasing number of legal challenges to government climate change policies are being advanced on the basis that states are violating the human rights or constitutional rights of applicants. A number of high-profile cases in Europe have upheld such claims and ordered governments to adjust their policies. But questions remain regarding how effective such rights-based cases may be in the effort to enforce climate change law obligations or encourage government responses to the crisis. This Article explores how such rights-based cases may exercise greater influence than is typically understood.

After explaining briefly the relevant human rights and climate change law, this Article examines in some detail a sample of rights-based climate cases that reflect a common pattern of features that provide the basis for such an explanation. The cases illustrate the incorporation of both international human rights law norms, and international climate change law obligations and standards, which are used to assess the legitimacy of government climate change policy. The courts increasingly rely upon the science of climate change institutions and the arguments and doctrines developed by foreign courts and international tribunals, including new doctrines for rejecting typical “drop in the ocean” causation and justiciability arguments traditionally relied upon to dismiss climate change cases.