(Initially published in The Japan Times, Aug. 18, 2010).

The prime minister’s advisory panel on national security has recommended a reconsideration of Japan’s adherence to the so-called three nonnuclear principles. The panel specifically urged that the third principle, the prohibition on the introduction of nuclear weapons into Japan (which forbids not only the stationing of weapons in Japan, but even the transit of weapons through Japan), be relaxed in order to permit the U.S. greater freedom in deploying nuclear weapons in Japanese territory.

This is a bad idea for many reasons, but for one it would be inconsistent with the Constitution.

As is well known, Article 9, paragraph 1 of the Constitution renounces war and the threat or use of force as sovereign rights of the nation, while paragraph two prohibits the maintenance of armed forces or other war potential, and denies to Japan the right of belligerency. The long established official understanding of paragraph 1 is that Japan can only use the minimum military force necessary for its individual self-defense. It cannot use or threaten the use of armed force for collective self-defense, or for U.N. collective security operations.

Even this understanding, long embraced by successive governments, the courts, and the Cabinet Legislation Bureau, is a strained interpretation of a clause that clearly prohibits those uses of force that remain sovereign rights under international law — which are limited to individual and collective self-defense, and collective security operations. But the proposed changes to the nonnuclear principles would violate Article 9 under even the official interpretation.

The three nonnuclear principles were articulated by the government of Prime Minister Sato in 1967, and formally adopted in a Diet Resolution. Japan went on to sign the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty in 1970 and ratified it in 1976. The nonnuclear principles caught the imagination of the Japanese people and quickly became powerful elements of the broader pacifist identity associated with the constitution. As the only victim of nuclear weapons, this stance also made Japan a powerful symbol for the nonproliferation movement. Sato won the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts.

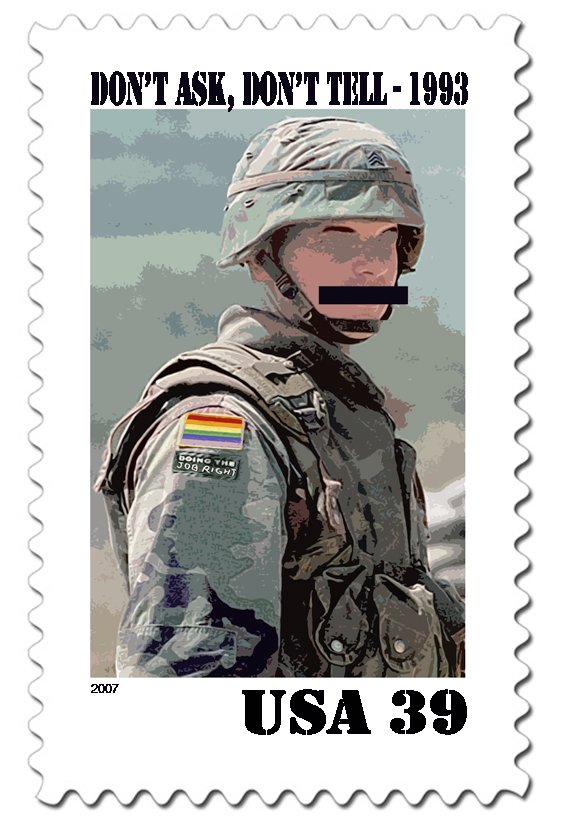

From banking to healthcare, looking to Canada has become fashionable of late. It is also an example on equality rights. I served as an officer in one of the first Canadian warships to deploy with women among its crew. That was only after a spirited campaign waged by the military against the integration of women in combat roles, in part on the basis that they would undermine the cohesion and fighting effectiveness of combat units. There would be privacy issues, sexual tension, an erosion of the essential masculine warrior ethos, and ultimately a degradation of military effectiveness.

From banking to healthcare, looking to Canada has become fashionable of late. It is also an example on equality rights. I served as an officer in one of the first Canadian warships to deploy with women among its crew. That was only after a spirited campaign waged by the military against the integration of women in combat roles, in part on the basis that they would undermine the cohesion and fighting effectiveness of combat units. There would be privacy issues, sexual tension, an erosion of the essential masculine warrior ethos, and ultimately a degradation of military effectiveness.