(Published in the HuffPost, July 17, 2017).

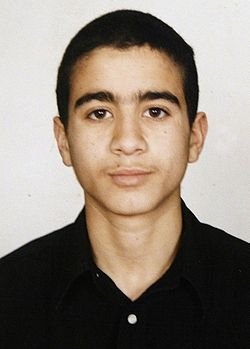

Much has been written both for and against the recent Khadr settlement, in which the Canadian government provided Omar Khadr with an apology and a $10.5 million payment. But the debate has largely focused on the wrong issue. Much of the discussion revolves around what Omar Khadr “deserves”—whether he deserved the treatment he received because he is a “confessed killer and terrorist”; or whether he now deserves the apology and payment because he is a “victim of torture and a denial of justice”.

As much as the settlement is about Omar Khadr and what he may deserve, it is more importantly about what Canada and Canadians deserve. An apology is not only for the benefit of the aggrieved, but for the integrity of the apologizer. Canada and Canadians deserves the atonement, the reaffirmation and restoration of our values, that is made possible by the settlement. Let me explain.

Canadian Values

The starting point has to be with our own values as a nation. What does Canada stand for, and what does it mean to be Canadian? We we are a liberal democratic country founded on constitutionalism, respect for human rights, and the rule of law. While the Charter of Rights and Freedoms has only been part of our constitutional system for some 25 years, surveys show that it has come to be the most significant determinant of Canadian national identity. This is likely because Canada has for much longer been a champion of international human rights, and international law more generally. In short, we are a nation that respects and embraces human rights.

We also inherited, as part of the British common law system, a deep respect for the rule of law. This is a term that is often bandied about but seldom defined or explained, but it is important here that we understand what it means. The rule of law is a complex concept consisting of many related principles, but two aspects are particularly important in thinking about the Khadr case: first, is the idea that there is a set of intelligible and accessible laws, established by regular democratic process, that apply equally to all within the system, including all branches of the government itself, and that are enforced fairly by regularly constituted courts. Second, under the more robust conception of the rule of law, individuals enjoy a number of fundamental human rights in their relationship with the state. Our Charter of Rights and Freedoms and adherence to international human rights treaties embody and codify this second aspect of the rule of law.

The Violation of Khadr’s Rights – Torture

So how does the Khadr case implicate these values? While there is some uncertainty about whether Omar Khadr did or did not cause the death of an American soldier in Afghanistan in 2002 (to which I will return below), there is no question that the treatment of Khadr violated a number of his most fundamental human rights. What is more, the Canadian government was determined by the Supreme Court of Canada (twice! here, and here) to have been complicit in several of those violations, such that it violated Khadr’s Charter rights.

First, and most seriously, Omar Khadr was subjected to torture, and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment, in violation of the Geneva Conventions of 1949 and the United Nations Convention Against Torture. Both at Bagram in Afghanistan and at Guantanamo Bay, Khadr was subjected to a number of the “enhanced interrogation techniques” that were condemned as constituting torture by the U.S. Senate Intelligence Committee and others. The European Court of Human Rights held that the conduct constituted torture, and ordered Poland to pay damages for its complicity in the process.

The Supreme Court of Canada later determined that Canadian government officials had been complicit in these violations because CSIS and DFAIT agents had participated in the interrogation of Khadr at Guantanamo Bay in 2003, knowing that American authorities had “prepared” Khadr for the meeting with sleep deprivation and other prohibited techniques. What is more, Canadian agents then passed on the fruits of that interrogation to American authorities. This is sufficient to end the analysis of whether Khadr was wronged. The prohibition against torture is a “peremptory norm” in international law, which can never be derogated from, and the violation of which can never be justified. Torture is repugnant to our most fundamental values, and history has shown that torture can corrode and corrupt the institutions and norms of a democratic society.

His Due Process Rights

Second, Khadr was denied access to fundamental due process. He was prosecuted in a military commission system that has been roundly condemned as being illegitimate and inconsistent with international law. The Supreme Court of the United States itself held, in Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, that the military commissions regime, as it was constituted during the years that Khadr was initially charged, violated American international legal obligations under the Geneva Conventions. Even after Congress tried to fix the worst problems with the military commissions, they were widely viewed internationally as being illegitimate ad hoc tribunals established to ensure convictions, entirely inconsistent with the rule of law.

Even leaving the court system itself aside, the charges against Khadr, which are the basis for his conviction under the plea agreement, were entirely invalid under international law. The jurisdiction of the military commissions were limited to violations of the laws of armed conflict, of which the most grave are called “war crimes.” But Khadr was charged with “crimes” that are not war crimes or violations of the law of armed conflict at all. he was charged with engaging in hostile acts while an “unprivileged belligerent”—meaning that he was a civilian taking direct part in hostilities. But that is not a violation of the law of armed conflict.

As a civilian Khadr had no authority to engage in hostilities, and so he could be prosecuted under Afghan or Canadian criminal law for murder or manslaughter if he killed a man in combat—but his participation in hostilities and even killing combatants is not a war crime, and it was not within the jurisdiction of military commissions to prosecute. Indeed, Harold Koh, then legal counsel to the U.S. State Department, objected to the charges on the very grounds that this legal theory meant that civilian CIA drone operators killing people in Yemen would be vulnerable to charges for the same offence. While his objections were rejected and the double standards ignored, the illegitimacy of these charges under international law are the basis for Khadr’s ongoing appeal in U.S. Federal Courts.

Finally, in relation to the violations of due process, the plea agreement and conviction on these invalid charges were procured on the basis of statements and confessions obtained through the use of torture and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment. It is a bedrock principle of fundamental justice in both international law and Canadian law that evidence obtained by torture is inadmissible. This is both because the veracity of the evidence itself is highly suspect, and because torture is so repugnant and reprehensible that to rely upon it brings the administration of justice into disrepute.

His Rights as a Child

Third, Omar Khadr’s fundamental rights as a child were violated. The foregoing violations would have been egregious enough had Khadr been an adult, but he was only fifteen years old when he was captured, and even younger when he was first recruited into Al Qaeda training camps in Afghanistan by his father.

Most legal systems treat children differently from adults, because it is recognized that children, even teenagers, are more vulnerable and not fully capable of responsible decision making, because they do not yet have completely developed cognitive abilities or emotional maturity. For this reason they are legally protected, and not held fully responsible for their actions in the way that adults are.

International law increasingly defines children as persons under the age of 18. It prohibits the recruitment and use of child soldiers, and views child soldiers as victims to be treated and rehabilitated, not perpetrators to be prosecuted for conduct that would otherwise constitute war crimes. The treatment of Khadr was also inconsistent with Canadian principles regarding the treatment of juveniles in the criminal context. The Supreme Court of Canada held that the participation of Canadian officials in the interrogation of Khadr “offended the most basic Canadian standards about the treatment of detained youth suspects.”

The Rule of Law

For all of these reasons we can conclude unequivocally that Omar Khadr’s international human rights were egregiously violated, and the Canadian government’s complicity in some of these violations meant that his constitutional rights under the Canadian Charter were also violated, as was twice determined by the Supreme Court of Canada. He was grievously wronged, regardless of whether he killed the American soldier as alleged.

These violations of his human rights are all deeply inconsistent with a “thick” conception of the rule of law, but the prosecution in irregular courts, on charges for which there is simply no offence in the legal system over which these courts have jurisdiction, and the denial that the same offences could apply to one’s own civilians engaged in combat, makes a mockery of the most basic principles of the rule of law.

Khadr’s “Guilt”

All of this means that Khadr was wronged, and Canada was complicit in that wrong, regardless of whether he killed a man in that firefight in Afghanistan. And to be clear, even if he did, it was no war crime, and no act of terrorism. It was at most a homicide under domestic criminal law. This could never justify the wrongs that were done to him. But the reality is that we actually do not really know whether or not Khadr killed the American soldier.

Khadr himself now says he cannot recall the events of that day, which is entirely plausible given the fact that he was seriously wounded in the firefight and then tortured shortly thereafter. Evidence has come to light that casts significant doubt on the allegation. It certainly has never been proven in any legitimate legal proceeding. And for reasons already explained, the “confession” and “guilty plea” should have very limited weight in thinking about the Khadr case—these were procured as the fruit of torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment, in relation to invalid charges, and under the coercive choice of being detained indefinitely in Guantanamo if he refused, or the prospect of a return to Canada if he plead guilty.

Restoring Canada’s Values

Some have argued that regardless of whether Khadr threw the grenade, he was fighting with terrorists, and different considerations should apply in dealing with terrorists. But that is entirely inimical to the bedrock principle that our laws and our constitutional rights apply equally to all. Nor is it relevant that “the other side” does not play by the same rules. That logic leads to a race to the bottom.

The great Israeli jurist Justice Aharon Barak wrote in a judgment prohibiting the physical abuse of detainees, that the rule of law and respect for civil liberties mean that democracies must fight with one arm tied behind their back, but they are nonetheless stronger for it. It is these values that terrorists seek to undermine in the first place, and which we are fighting to defend, so it makes no sense to violate them in the process of trying to defend them.

In sum, I would suggest that Omar Khadr does indeed deserve an apology and compensation for the egregious violations of his rights. But more importantly, Canadians deserve the government’s reaffirmation of our nation’s values, the recognition that our rights are inviolable and sacrosanct, and the demonstration that the rule of law remains strong in Canada, even as it comes under threat elsewhere in the world.