(Published in The Huffington Post, May 19, 2011)

The torture debate has once again seeped into the public discourse in America, and it has us focusing once again on all the wrong issues. Suggestions have been made that information that Khalid Sheikh Mohammed provided while being water-boarded helped lead the CIA to bin Laden’s door. This has prompted the likes of John Yoo (author of the notorious torture memos signed by Jay Bybee) and former Attorney General Michael Mukasey, to argue that the case for water-boarding has been vindicated. Others, including Senator John McCain, have refuted the assertions that the trail to Bin Laden can be traced back to so-called “enhanced interrogation techniques.” In short, the debate is once again centering on the question of whether torture is effective.

First, it should be noted that the debate misconstrues the effectiveness argument. Few people would assert that torture can never produce so called “actionable intelligence.” The point, made extensively by FBI interrogators and other specialists in the field, is that torture produces less reliable intelligence than traditional (and lawful) methods of interrogation, since the victim will say anything to avoid the pain, some of it true but much of it not, creating the problem of trying to distinguish between fact and fiction. Moreover, a policy of torture creates longer term strategic costs in the effort to win over hearts and minds, which ultimately makes it counter-productive and ineffective from a broader perspective.

The key point, however, is that effectiveness is entirely beside the point. We should oppose and reject the use of torture even if it could be shown that it is effective. To his credit, John McCain also makes this argument. For those who do oppose torture, it is a profound mistake to be engaging in this debate about effectiveness. First of all, the arguments get reduced to the overly simplistic and binary question of whether it ever works, which is of course vulnerable to attack — just one example of torture producing one piece of accurate intelligence tends to undermine the entire position. Hence the debate today. But more importantly, engaging in this debate tends to suggest that if torture were found to be effective, then perhaps we might have to use it. But we would not, or should not, so why get trapped in this debate? We ought to stick to the real reasons for our objections.

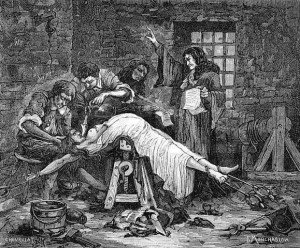

So what are the real reasons for rejecting torture? The first is that it is abhorrent to both the principles underlying the rule of law, and our understanding of fundamental human rights — both of which are cornerstones in the foundation of our democracy. The common law rejected the practice of torture, and the admission of any evidence procured by torture, as early as the fifteenth century. It did so not only on the grounds that the information so obtained was inherently unreliable, but also because it was felt that the practice of torture would degrade all those who engaged in it, ultimately undermining the authority and effectiveness of the judicial system itself. And indeed, the continued use of torture by the Star Chamber in the sixteenth century became one of the central issues between the Crown and Parliament, with torture being cited as being “totally repugnant to the fundamental principles of English law… and repugnant to reason, justice, and humanity.” That view, of course, informed the drafting of the 8th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

With the development of human rights law in the twentieth century the prohibition against torture was embedded in international law conventions. This reflected the recognition that to torture another human being is not only to treat them as being less than human, and to destroy aspects of their physical and mental integrity, but it is also to degrade and undermine the humanity of those who perpetrate the torture. The U.S. was a harsh critic of regimes that engaged in torture in the past. The prohibition against torture has become one of only four or five “peremptory norms” in international law — norms that apply to all states and which cannot be derogated from by any state, for any reason. The U.S. helped to champion these norms and develop the treaty regimes that support them. The other peremptory norms include the prohibitions against genocide, slavery, crimes against humanity, and piracy. Would we really countenance a debate on the possible effectiveness of genocide or slavery?

The purported moral arguments trotted out in support of torture are in fact fallacious. In the context of the famous ticking time bomb hypothetical, it is argued that it is surely moral to torture one person in order to save the lives of thousands — that the right to life trumps the right to physical integrity and security of the person. The problem of course is that this is a false construct. We will virtually never be in a situation in which we know for certain that a person has specific information which, if obtained through torture, we know will definitely save the lives of a specific set of people. At most we will think that we know that the person might have information, which may help us save some undetermined lives. Like the CIA officials who “knew” that Abu Zoubayidah was a high-level al Qaeda operative, certain to have crucial information, which would absolutely save American lives, when they ordered him water-boarded 83 times – only to discover that he was never even a member of al Qaeda, and that he had no such information. As a matter of morality it is not justifiable to torture one person on the mere possibility that it might save the lives of some unknown people, and a hypothetical that will virtually never occur is no basis for a public policy.

In short, we should reject torture because it is contrary to the fundamental principles underlying the rule of law and our understanding of human rights. It is utterly inconsistent with the values that form the foundation of our democracy. It will degrade us as a people. The experience of countries that have in the past century adopted the use of torture for “national security” purposes, illustrate how the policy seeps into other areas of the judicial system, corroding the integrity of criminal justice and undermining the authority of the state. The proponents of torture are no doubt animated by the desire to protect the people and interests of the United States. What they fail to understand is that the strategic objective of terrorism is to gut our value system and destroy the foundation of our democracy. Engaging in torture only helps them achieve their aims. Frankly, even having the debate is harmful to our national interests. We cannot champion the rule of law and espouse the benefits of democracy while we argue at home about whether to torture people.