There was a remarkable discovery announced just this week, that documents uncovered in American archives reveal that the U.S. ambassador to Japan in 1959 actively interfered in the judicial process regarding the determination of a fundamental constitutional issue. While the discovery has been widely reported in Japan, the context and significance of the issue deserve to explored in more depth.

The case in question, commonly known as the Sunakawa case, remains a highly important judgment of the Supreme Court, and the discovery that the U.S. government interfered in the process is important, and may have political repercussions in the ongoing constitutional revision debate.

The Telegram

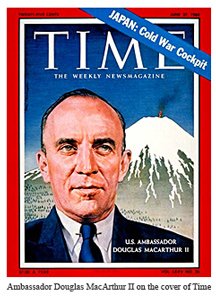

The discovery itself was made by a Japanese historian on U.S. Japanese relations named Niihara Shoji. While doing research at the U.S. National Archives he uncovered a telegram from ambassador Douglas MacArthur II, nephew to the more famous general who was Senior Commander Allied Powers during the occupation of Japan. In the telegram, sent to Washington in April, 1959, ambassador MacArthur recounted his discussions with both foreign minister Fujiyama Aiichiro, and with Supreme Court Chief Justice Tanaka Kotaro, regarding the ruling by the Tokyo District Court in March, 1959, that the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty was unconstitutional, and that the maintenance of U.S. armed forces in Japan was a violation of Article 9 of the Constitution.

The telegram explains that ambassador MacArthur had initially pressed foreign minister Fujiyama to ensure that the government would appeal the decision directly to the Supreme Court, by-passing the more normal procedure of appealing to the Tokyo High Court. According to the telegram, he “stressed importance of GOJ [government of Japan] taking speedy action to rectify ruling by Tokyo District Court”.

It also recounts how he then had private discussions with Chief Justice Tanaka, after the Supreme Court was seized of the case, in which he sought to determine when the Supreme Court would likely hand down its decision. While the telegram is apparently silent on the issue, it is difficult to believe that the ambassador would not have similarly conveyed to the Chief Justice the American view that it was essential to “rectify” the ruling of the court below.

Why the need for speed? How important a case was this? Why should this be viewed as being important now, some 48 years later?

The Context of the Sunakawa Case

First a few words on the case itself. It was a criminal trial involving the prosecution of several people for trespassing on the property of a U.S. forces base, which they had done in the course of demonstrations against the presence of U.S. forces in Japan and the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty itself. They were prosecuted under a special law that carried a higher penalty for trespassing on U.S. forces property than the penalty provided for trespassing under the regular criminal law.

The accused challenged the constitutionality of the law on the grounds that it had been passed pursuant to and in support of the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty, which they argued was in violation of Article 9 of the Constitution. Art. 9 prohibits the use of force and the maintenance in Japan of any land, sea, or air forces, or other war potential. The Tokyo District Court held that the U.S. forces in Japan constituted such armed forces and thus violated Art. 9, and that the treaty that required Japan to permit such maintenance of U.S. forces was similarly in violation of Art. 9.

The government of Kishi Nobusuke was in the midst of re-negotiating the treaty, and it was up for renewal in 1960. There were increasing protests and demonstrations against the treaty and the presence of U.S. forces, of which the accused in the case had been a part. The protests continued to mount in 1959, with strikes, student demonstrations, and even violent confrontations escalating as the year wore on. Meanwhile, in the midst of the Cold War, the U.S. government viewed the continued maintenance of substantial U.S. forces in Japan as crucial, and hence the need for speed in “rectifying” the decision of the lower court in this case.

The Supreme Court Decision

The Supreme Court handed down its decision in the Sunakawa case in December, 1959, on the very eve of the final conclusion of the renewed U.S.-Japan Security Treaty. In comparison to normal timelines for Japanese litigation, to have a Supreme Court decision some 9 months after the decision of first instance represents unprecedented and blinding speed. Ten years is much more typical. This is significant in the context of considering the influence the U.S. government may indeed have had on the process.

The decision itself remains profoundly important in Japanese constitutional law. The Court overturned the decision of the Tokyo District Court, and remanded the case. Far more importantly, however, the Court engaged in an interpretation of Art. 9 for the first and only time in its history (before or since), and made a determination that continues to influence the institution of judicial review more generally.

The majority of the Court held that notwithstanding the apparent meaning of Art. 9 on its face, it did not preclude Japan from exercising individual self-defence, and it was open to Japan to establish agreements with other countries for the purpose of providing for its defence. Moreover, it held that since the U.S. forces were not under the command and control of the Japanese government, they did not constitute the maintenance by Japan of land, sea or air forces, or other war potential in violation of Art. 9.

But far more important, the real basis of the decision was that the question itself was not properly within the jurisdiction of the courts, because the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty had such a degree of “political consideration”, and thus the question of its constitutionality was too “political”, such that the courts could not make the determination and had to defer to the executive and legislative branches of government on the issue.

The Court came to this view notwithstanding that Art. 81 of the Constitution provides that the Supreme Court has the sole authority to interpret the Constitution and to determine the constitutionality of any law, regulation, or other act of government, and that Art. 98 of the Constitution provides that it is the supreme law of the land, and that no law, regulation, or other act of government that is inconsistent with it will have any force and effect.

The narrow question before the Court was whether the provisions of the treaty that required Japan to permit the maintenance of U.S. forces in Japan were inconsistent with Art. 9(2) of the Constitution, such that the legislation passed to support such forces, were therefore invalid, and that was clearly a legal question. Yet the Court ducked it, and held that it was “too political” because it had ramifications that affected Japan’s international treaty obligations and its relationship with the U.S. As Justice Kotani wrote in an impassioned dissent (on the reasoning, not the result), in effect the Court was taking the position that any issue of significant importance was beyond its jurisdiction and should be deferred to the executive and legislative branches.

The Significance of the Decision

While the Supreme Court has never itself explicitly made recourse to this “political question” refuge (and it should be made clear that the reasoning behind it has little resemblance to the ‘political question doctrine’ employed in U.S. jurisprudence), the lower courts have repeatedly used it, often in the course of dismissing claims regarding Art. 9.

Thus, in my view, the Supreme Court judgment in the Sunakawa case not only operated to eviscerate the normative power of Art. 9, and thus helped to undermine the integrity of the Constitution, but it very badly damaged the power of the judiciary and the institution of judicial review itself. As Justice Kotani in dissent argued, the Court could have reached the same result, by simply finding that U.S. forces did not constitute the maintenance of forces by Japan, without going the additional step of depriving itself of jurisdiction to interpret the constitutionality of the treaty, or other politically important issues.

The Implications of the U.S. Interference

Now we discover that the U.S. government most improperly interfered in the process of the case. We still do not know the extent to which pressure was brought to bear on the Supreme Court of course, nor the extent to which it would have been susceptible to overt pressure from Americans in any event. But there is no question that the Court understood the difficulty of the position it was in, given that it was in a real sense being asked to issue a judgment that would require the government to either abrogate or violate its international treaty obligations on the one hand, or stand in violation of the Constitution in a manner that could not be remedied on the other.

The U.S. interference would have made the difficulty of this position all the apparent and poignant. And reflecting yet again the old saw that justice must not only be done, but be seen to be done, the discovery that the U.S. government was interfering with a Supreme Court deliberation on this most important of cases, may reverberate in the ongoing debate over constitutional revision.