There was a remarkable discovery announced just this week, that documents uncovered in American archives reveal that the U.S. ambassador to Japan in 1959 actively interfered in the judicial process regarding the determination of a fundamental constitutional issue. While the discovery has been widely reported in Japan, the context and significance of the issue deserve to explored in more depth.

The case in question, commonly known as the Sunakawa case, remains a highly important judgment of the Supreme Court, and the discovery that the U.S. government interfered in the process is important, and may have political repercussions in the ongoing constitutional revision debate.

The Telegram

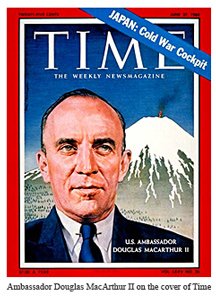

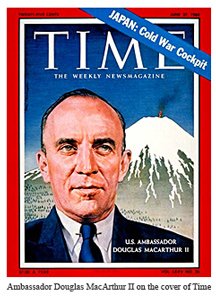

The discovery itself was made by a Japanese historian on U.S. Japanese relations named Niihara Shoji. While doing research at the U.S. National Archives he uncovered a telegram from ambassador Douglas MacArthur II, nephew to the more famous general who was Senior Commander Allied Powers during the occupation of Japan. In the telegram, sent to Washington in April, 1959, ambassador MacArthur recounted his discussions with both foreign minister Fujiyama Aiichiro, and with Supreme Court Chief Justice Tanaka Kotaro, regarding the ruling by the Tokyo District Court in March, 1959, that the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty was unconstitutional, and that the maintenance of U.S. armed forces in Japan was a violation of Article 9 of the Constitution.

The telegram explains that ambassador MacArthur had initially pressed foreign minister Fujiyama to ensure that the government would appeal the decision directly to the Supreme Court, by-passing the more normal procedure of appealing to the Tokyo High Court. According to the telegram, he “stressed importance of GOJ [government of Japan] taking speedy action to rectify ruling by Tokyo District Court”.

It also recounts how he then had private discussions with Chief Justice Tanaka, after the Supreme Court was seized of the case, in which he sought to determine when the Supreme Court would likely hand down its decision. While the telegram is apparently silent on the issue, it is difficult to believe that the ambassador would not have similarly conveyed to the Chief Justice the American view that it was essential to “rectify” the ruling of the court below.

Read more

It is useful to compare this position with the 1995 judgment of the Supreme Court of Israel, in which the Court rejected government arguments that it could find ex ante authority for harsher interrogation techniques in the principle of necessity.

It is useful to compare this position with the 1995 judgment of the Supreme Court of Israel, in which the Court rejected government arguments that it could find ex ante authority for harsher interrogation techniques in the principle of necessity.