Canadian Supreme Court Repudiates the Legal Black Hole Paradigm

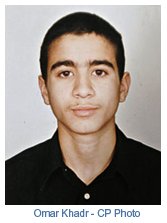

The Supreme Court of Canada handed down a judgment relating to detainees in Guantanamo Bay on May 23, holding that the one Canadian detained there may rely upon the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms to obtain some due process protection from the Canadian government.

Overview

The decision has already been reviewed briefly from the perspective of Canadian constitutional law on the University of Toronto and Osgoode Hall law school blogs, so I will not repeat that process here. But the decision has importance from the perspective of international law, and the relationship between international and constitutional law.

I would suggest that the judgment refutes the arguments, voiced most  recently by several scholars at the ASIL conference in April, that there are circumstances in the so-called “war on terror” in general, and the treatment of detainees in particular, in which neither constitutional law or international law (whether human rights or humanitarian law) ought to govern the conduct and procedures of the detaining forces.

recently by several scholars at the ASIL conference in April, that there are circumstances in the so-called “war on terror” in general, and the treatment of detainees in particular, in which neither constitutional law or international law (whether human rights or humanitarian law) ought to govern the conduct and procedures of the detaining forces.

The Supreme Court held that it is precisely when the agents of the Canadian government participate in conduct and circumstances that constitute violations of international law, that the application of the Charter will be triggered and its protections available to detainees (or at least Canadian detainees – more on that distinction below).

Background

Omar Khadr was 15 years old when he was captured by U.S. forces in Afghanistan in July, 2002. He was one of the few detainees who has been arraigned and who is actually moving towards a trial before the much-disputed Military Commissions in Guantanamo Bay. He has been charged with murder and with conspiracy to commit other acts of murder and terrorism. The murder charge arises from the death of a U.S. soldier during the skirmish in which he was captured.

The Supreme Court decision was in respect of an application by Khadr for full disclosure of all information in the hands of the Canadian government that may be relevant to his case. He had been interviewed and interrogated by officials of the Canadian government in Guantanamo Bay, and the evidence reflected that the Canadian government had shared some of the information so obtained with the U.S.

The importance of disclosure to his case before the Military Commissions is difficult to overstate, as detainees obtain only very limited disclosure from the prosecution. After the U.S. Supreme Court held that the procedures of the Military Commissions were unlawful in its decision in Hamdan v. Rumsfled (2006), Congress promptly passed the Military Commissions Act to provide the legislative authority for most of those same procedures. They included the admissibility of evidence obtained through “coercion”, denying the accused access (even at the hearing itself) to classified evidence, and even excluding the accused from the hearing in certain circumstances. The disclosure obligations on the prosecution are very limited.

There has yet to be a full trial before the Military Commissions, but the conduct of the Combat Status Review Tribunals (CSRT), which were created to determine whether detainees met the definition of “unlawful combatant” for the purpose of prosecution, have been analyzed by a team at Seaton Hall Law School (report here). The denial of the most fundamental rights expected in administrative and judicial proceedings was found to be extreme, and is suggestive of the entire Military Commission process.

Indeed, the D.C. Circuit Court held in Bismillah v. Gates (2007), that the lack of disclosure by the government in judicial review proceedings of CSRT decisions was unconstitutional. But there is little relief in sight with respect to the lack of due process in the Military Commission hearings themselves (the other significant Guantanamo case before the U.S. Supreme Court, Boumediene v. Bush, in which Khadr is also a party, relates primarily to the legality of the provisions of the Military Commissions Act that purported to strip the federal courts of habeus corpus jurisdiction with respect to detainees). Thus any disclosure Khadr can get from the Canadian government will be helpful for his case.

The Decision

Khadr sought full disclosure from the Canadian government, on the grounds that section 7 of the Charter governed his relationship with the Canadian government. Section 7 of the Charter, which provides for the “right to life, liberty and security of the person and the right not to be deprived thereof except in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice”, was interpreted in the seminal case of R. v. Stinchcombe (1991), as requiring the government to provide the accused in a criminal proceeding, whose liberty interests are thus at stake, with full disclosure of all material relevant to the issues in the case. The government argued that the Charter did not apply to the operations of government officials operating abroad, and that Stinchcombe was thus irrelevant.

In deciding the case in Khadr’s favour, the Supreme Court expanded an exception it had created in R. v. Hape (2007), the case which revised the general principles for Charter  application to the conduct of government officials abroad. The basic rule is that the Charter will not apply, due to the deference owed to the laws of the foreign jurisdiction in which the Canadian agents are operating. Such deference, manifested by refraining from any attempt to extend the operation of one’s own laws to conduct within a foreign jurisdiction, is required by the principle of comity in international law. But the Court held in Khadr that where the conduct in which the Canadian agents are participating violates international law (and more specifically Canada’s international law obligations), then the basis for deference is negated, and the Charter will apply to the extent of the participation.

application to the conduct of government officials abroad. The basic rule is that the Charter will not apply, due to the deference owed to the laws of the foreign jurisdiction in which the Canadian agents are operating. Such deference, manifested by refraining from any attempt to extend the operation of one’s own laws to conduct within a foreign jurisdiction, is required by the principle of comity in international law. But the Court held in Khadr that where the conduct in which the Canadian agents are participating violates international law (and more specifically Canada’s international law obligations), then the basis for deference is negated, and the Charter will apply to the extent of the participation.

Rather than engage in an independent inquiry into the extent to which conduct in Guantanamo Bay violated international law, the Court simply relied upon the decisions of the Supreme Court of the United States in Rasul v. Bush (2004) and Hamdan v. Rumsfeld(2006) as the basis for finding that the deprivation of habeus corpus, and the procedures established for the operations of military commissions, were in violation of international law and illegal under U.S. law during the period in which Canadian agents interrogated Khadr in Guantanamo.

As such, the Court held that “the regime providing for the detention and trial of Mr. Khadr at the time of the [Canadian interviews] constituted a clear violation of fundamental human rights protected by international law.” (para. 24) Canadian agents participated in that activity, which would have clearly been a violation of Khadr’s Charter rights had it occurred in Canada, and the violation of international law by the U.S. negated the deference that would otherwise prevent application of the Charter.

The crux of Canadian participation in the process was the obtaining information from Khadr and providing it to the U.S. Thus, the Court reasoned, the refusal to disclose the information related to those interviews was a breach of section 7 of the Charter, and Khadr’s remedy is to obtain disclosure of that information, subject to possible privilege claims (the remedy is significantly narrower than that sought, which was disclosure of all relevant information in the government’s possession – it is entirely unclear to me why the order would not at least also include any information that the government received from the U.S. in the course of the interviews and information exchanges related thereto).

Significance

As indicated above, it seems to me that this decision refutes the arguments of some in the U.S. that the treatment of detainees in such places as Guantanamo, Afghanistan and Iraq, should not be subject to either the constitutional law of coalition countries, or international law. Moreover, as discussed elsewhere in these posts, the U.S. has undertaken efforts to ensure that detainees will not even have access to any protections afforded by the local legal system in Afghanistan either (and of course there is no other legal system available in Guantanamo), thus leaving them with virtually no legal protection whatsoever.

These arguments in essence suggest that constitutional law ought not to apply, since the nexus of citizenship, presence within the jurisdiction and so forth, do not exist to trigger its operation in respect of detainees. At the same time, since they are not lawful combatants in an international armed conflict, the laws of international humanitarian law should not apply. But since they are being detained in the “war on terror”, which is an armed conflict of a sort (or so the argument goes), international human rights law ought not to apply either. There is thus, according to these arguments, a legal black hole in which detainees can be afforded the most limited procedural protection and due process, entirely at the discretion of the detaining power.

The Supreme Court of Canada decision in this case, it seems to me, stands in stark contradiction to such arguments, with its holding that Canada’s constitutional protections and remedies will be applied by the Canadian courts precisely when it is determined that international law has been violated. In essence, rather than accepting the notion that these are circumstances in which no law will be deemed to apply, the Court has recognized what is effectively double coverage: international law is recognized as governing the treatment of detainees generally, and when it has been violated in circumstances in which agents of the Canadian government have participated, the Canadian Charter will also be applied to the extent of that participation.

As Sujit Choudhry notes in his initial discussion of the case (in the University of Toronto blog cited above), that will likely inform the Court’s pending analysis of Canada’s obligations to non-Canadian detainees captured by Canadian Forces in Afghanistan. The distinction there, of course, will be that the detainees are not Canadian, and the Court will not have U.S. precedents to rely on in assessing the question of Canadian participation in violations of international law. The issue of Canadian Forces’ compliance with the Geneva Conventions will be squarely before the Court, and it will be interesting to see whether the nationality of detainees will become a significant factor in the Charter analysis.

Thus, while there has been some early criticism of the decision (e.g. the Osgoode Hall blog noted above, which questions why the broader aspects of the government’s participation, and failure to act, in the Khadr case remains largely unexamined), from the perspective of the relationship between international and constitutional law, particularly in the context of the treatment of detainees in counter-terrorism efforts, the case may be viewed as a positive step, and one more blow against the black hole paradigm.